The Grassmarket was one of fifteen different markets within the city of Edinburgh, formed under the 1477 ordinance of King James III [1460-1488]. For example, cotton and linens were sold in the Lawnmarket; corn in the Cowgate; cattle in King’s Stables Road and so on. The sale of live animals was forbidden in the town, and this was why cattle were to be sold outside the city wall at King’s Stables Road. This road was so named because the Royal horses were kept at the base of the Castle Rock, and tournaments and the like were held there, particularly in the reign of James IV [1488-1513]. The area was acquired by the City in 1663 and cattle and horses continued to be sold there even when a cattle market was established in Lauriston Place in 1843. The Lauriston Place cattle market was partly demolished for the building of the Fire Station in 1900 and the remainder removed so that the Edinburgh College of Art could be established in 1907. The horse and cattle markets were held weekly from 1477 until 1911.

The Grassmarket occupies that part of Edinburgh forming the southern valley, which lies between the eastern portion of Highriggs (the elevated area of ground lying south of the West port and Grassmarket, on a part of which George Heriot’s Hospital was built) and the ridge forming Castle Hill. It is in the form of a rectangle and within the original City Walls of Edinburgh, the Grassmarket occupied the largest open space. At the southeast corner, it is continuous with the ancient Candlemaker Row and the southern portion of the Old Town, with another route through Cowgatehead to the Cowgate. Candlemaker Row passed from the Bristo (or Greyfriars) port down to the southeast corner of the Grassmarket, at its junction with the Cowgate. At the northeast corner is the steep entry to what was the West Bow. Following the construction of George IV Bridge in 1827, Victoria Street was built to allow easier access to the High Street from the Grassmarket, by way of George IV Bridge, but originally the West Bow ran up from the Grassmarket to emerge at the junction of Castlehill and the Lawnmarket, where it was initially known as the Head of the Bow, and latterly the Upper Bow.

The archway of the ancient West Port in the southwest corner of the Grassmarket, gave its name to the West Bow, because a bow was the name given to an arch. The butter and cheese market of King James III was in the Lawnmarket, at the Head of the Bow. To the north, the Grassmarket is bounded by the precipitous slopes of Edinburgh Castle, and on the south by the much gentler slopes of the adjacent Greyfriars, Tolbooth and Highland Kirk and the turreted George Heriot’s School, formerly George Heriot’s Hospital.

The western end of the Grassmarket was long closed up, and encroached upon by the Corn Market, a large building some 80 feet long by 45 feet in width (24.6 x 13.8 metres), with a central belfry and clock, which was eventually demolished. The old Corn Market was at the eastern end, the poorer part of the Grassmarket, and an area reflecting a shameful part of the history of Scotland, where many Covenanters died in their defence of the Church. Access to and from the Grassmarket at the west end is currently via the West Port at the southwest, and King’s Stables Road to the northwest. There were several ports (or gates) in the city walls; all of these were in a ruinous state by 1745. These included the aforementioned West Port; Greyfriars (or Bristo) port, on the site now occupied by the Bedlam Theatre, at the junction of Bristo Street and Forrest Road. This was formerly the New North Church and a former site of the lunatic asylum known as Bedlam; the Potterrow port, between the University of Edinburgh Old College and the Royal Scottish Museum; the Cowgate port, at the junction of the High Street and St Mary’s Wynd (now Street); and the New or Halkerston’s Wynd port, at the south end of the foundations for the North Bridge. The Corn Exchange was situated on the Grassmarket from 1716 until 1852, and was sited at the rear of the Flodden Wall. The New Corn Exchange was built in 1849 and occupied the site that is now 31-35 Grassmarket. The general shape of the Grassmarket is little changed from that of medieval times.

Current vehicular entrances to The Grassmarket are from The West Port, King’s Stables Road, Victoria Street, Cowgatehead and the Cowgate, and Candlemaker Row.

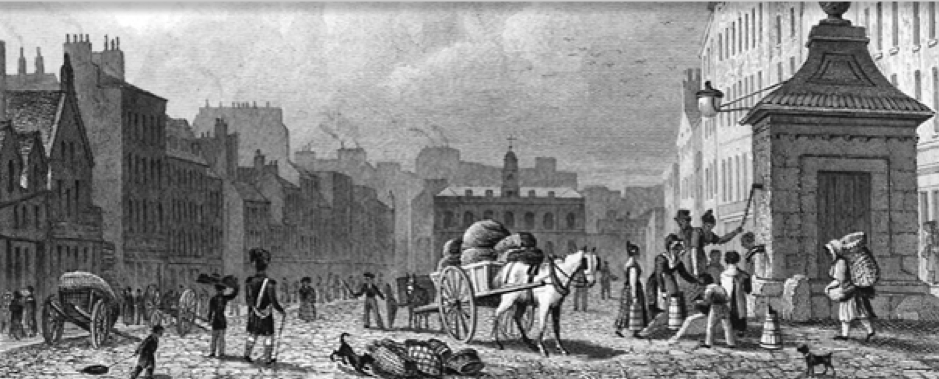

In the 19th century, the Grassmarket was a meeting place for carriers and farmers, together with those associated with the county house and cattle markets, and presented an airy, busy and imposing appearance. It was a mix of architecture, showing turnpikes, crow-stepped gables, massive chimneys, and old signs. The fact that this was to be assigned as a weekly market was dated to 1477, when King James III ordained that ‘wood and timber be sold ‘fra Dalrimpil yarde to the Grey Friars and westerwart; alswa all old graith and geir to be vsit and sold in the Friday market before the Greyfriars lyke as is usit in uthir cuntries’.

This part of the city was first paved in 1543 at a cost of 26 shillings and eight pence (approx £1.33) per rood (approx 0.1 of a hectare), from the Upper Bow to the West Port. 16th century granite setts were laid down in the middle of the causeways. In 1828, close to the West Port, was a suburb of the same name, and it was the scene of the grave-robbing and murders carried out by the infamous William Burke and William Hare, who lived in Tanner’s Close, near Lady Lawson Street, although Log’s Lodgings, in Tanner’s Close, run by Margaret Laird and William Hare was also reported to be in the West Port.

In 1650, the City Magistrates moved the Corn Market from its then site at Marlin’s Wynd (now Blair Street), to the east end of the Grassmarket, where it continued to be held until the late nineteenth century.

Around about 1660, the Grassmarket began to acquire a gloomy character, as public executions of persons based on religious intolerance began to take place, together with those of sundry criminals. Castle Hill and the Market Cross had previously been the sites chosen for such executions, which were initially carried out by beheading with a sword, prior to the introduction of ‘The Maiden’ (a Guillotine), which was last used in 1710.

Many of those executed were Covenanters, and this continued on an almost daily basis until 17th February 1784, when James Renwick was executed for disowning an uncovenanted King. In excess of a hundred covenanters were executed here, the site now marked by a memorial stone. The Duke of Rothes remarked ‘Then let him glorify God in the Grassmarket’, when a covenanter proved obdurate, since such deaths were usually accompanied by much psalm singing. Ironically Alexander Cockburn, the city hangman, murdered a King’s Blue Gown (also known as Bedesmen; these were privileged beggars) and died in the Grassmarket, where he had hanged so many others.

In the early 18th century, a woman fish hawker who was to become known as ‘Half-hangit’ Maggie Dickson was found guilty of concealing her pregnancy and delivery of a premature child. She had been tried under a Concealment of Pregnancy Act of 1690. Sentenced to death, she was hanged in the Grassmarket on the 2nd September 1724, but was apparently revived in her coffin by its movement, when it was being taken away, and she survived her ordeal. Living in Musselburgh, where many came to see her, and having several other children, she lived for another 40 years as an inn-house keeper and as a crier of salt in the Edinburgh Streets. It was thought that she might have seduced the ropemaker to manufacture a weaker noose. The public house in the Grassmarket called Maggie Dickson’s was named in her memory.

Robin Oig Macgregor, one of the four sons of Rob Roy Macgregor, was executed in The Grassmarket in 1734 for the abduction of Jennie Kay, although retrospectively it seems that this charge was far from proved.

Four people, including Andrew Wilson and George Robertson, robbed the Collector of Customs at Pittenweem and were caught, tried, and Wilson and Robertson were sentenced to death, with no hope of a pardon. With the help of two others held in the Tolbooth for stealing horses, they tried to escape by bending the bars, but when Robertson tried to leave he was too big a man, and became stuck while attempting to bypass the stanchions in the window. When re-imprisoned, he was full of remorse for the fact that he had prevented the others from escaping. On the Sunday before their scheduled execution, they were escorted to St Giles Cathedral, as was the custom, when the sermon was directed to them. Their escort comprised four men of the City Guard, armed with pikes, and Wilson grabbed two of them in his hands and a third by his teeth. Robertson then knocked the fourth man down and made his escape. It was felt that an attempt might be made to secure the release of Wilson, and so he was taken to the Gibbet in the Grassmarket in the company of a strong body of the City Guard, and a detachment of the Welsh Fusiliers were also in evidence. Once Wilson had been hung, the Grassmarket mob attacked the City Guard and tried to steal Wilson’s body (he was later buried at Pathhead on the 5th April 1736). The Magistrates fled and the mob carried all before it. Captain John Porteous had felt that the escape of Robertson was an imputation on the City Guard and so, as they were returning up the West Bow, with the mob in pursuit, he ordered them to fire a first volley, which killed five or six people, and then a second because the mob were totally outraged, with around 30 people being wounded. Porteous was charged with this unlawful killing and on the 5th July 1736 sentenced to die on the 8th September 1736. In the absence of King George II, Queen Caroline, who sympathised with Porteous, granted a six-week reprieve, via the Home Office and Sir Robert Walpole, at the end of which time he was to be set free. The citizens felt that this Royal intervention was proof that the English government were disposed to treat this murder of Scottish citizenry as a minor offence, and so they decided that he should not escape punishment. A new mob now blocked off the street and advanced on the Tolbooth where, having failed to break down the door, they set it on fire and located Captain Porteous. They then took him back to the Grassmarket, breaking into a shop on the way, where they removed a length of rope, leaving the owner a guinea. At the Grassmarket, since the gibbet was not in place, they hanged the unfortunate Captain Porteus from a dyer’s pole near the east end of the Grassmarket just before midnight on the 10th of September, and then melted away into the shadows. The unfortunate Captain Porteus had been led, frantic and shrieking, into the Grassmarket, by the infuriated mob. He was buried in Greyfriars Churchyard on the 11th September 1736, with only a wooden post marked P.1736, but an inscribed headstone replaced this in 1973.

William Thomson and John Robertson murdered Helen Bell, servant to John Strachan, who had a house in the High Street, and then made off with around £1,000 in cash. Thomson was caught, tried and executed, while Robertson apparently escaped (having tried to murder Thomson, the latter refusing to set fire to Strachan’s house after the burglary). He gave his name to Thomson’s Court, in the Grassmarket.

One of the last persons to be hanged from the Grassmarket Gallows was James Anderson, on the 4th February 1784, for a robbery that he had committed in Hope Park. After this, Alexander Stewart, a 15-year old youth found guilty of robbery, was found guilty and sentenced to death. At the time, the judge stated that he was to be hanged in the Grassmarket, or any other place the magistrates may appoint, suggesting that, at the time, they were considering a change in the place in which public hangings were to be carried out. Accordingly, the west end of the old Tolbooth was set up for his execution, on the 20th April 1785.

Until 1823, there remained at the east end of the Grassmarket a massive sandstone block, in which there was a central square hole, as the socket for the gallows-tree, but this was replaced by a St Andrew’s Cross in the causeway to mark the exact spot. This also acted as a memorial to over 100 covenanters, who were hung and subsequently dismembered here for their beliefs.

The first Edinburgh Wall (the King’s Wall) was constructed in 1450, and the second (Flodden) Wall was built after the disastrous battle of Flodden, in 1513. The Flodden wall, in part, passed from the Castle down to the West Port, then up the Vennel to Lauriston, from there passing via Teviot Row to Bristo Port.

From the Cowgate, passing under George IV Bridge, via Cowgatehead, the road enters the Southeast corner of the Grassmarket. In the northeast corner of the Grassmarket are the remains of what used to be one of the most picturesque streets in Old Edinburgh, the former West Bow, now named (in part) Victoria Street. This was originally Z-shaped and gave access from the western corner of the Lawnmarket (at the foot of Castlehill), to the northeast corner of the Grassmarket. One of the more notable inhabitants of the West Bow or, more correctly, the Upper Bow, was the notorious Major Weir, or ‘Angelical Thomas’, who, like Deacon Brodie, was a man of two characters – a Covenanting soldier and one of the Godliest of men, regularly attending local Protestant prayer meetings and being accepted as a pillar of Edinburgh society. However, during an illness, and in a feverish state of mind, details of his other life became known to those who were attending him. He was hanged and burned as a witch in 1670, after he confessed to the organization of a coven and committing crimes of the most obscene depravity, including necromancy and supernatural activities, which included witchcraft. His sister Jean was also hung because she was his partner in these black arts. They were both tried on the 9th April 1670, and sentenced to death. Instead of asking for God’s mercy, he is believed to have said ‘let me alone – I will not – I have lived as a beast and must die as a beast’. Following his death, his house at number 10 West Bow remained unoccupied for a century, – an object of horror and reputed haunting, with neighbours confirming sightings of his ghost, with strange lights and sounds of laughter and revelry. This house was swept away, like most of the West Bow, in 1829, when access to the High Street was to be via George the IV Bridge rather than up to the west end of the Lawnmarket, and was renamed Victoria Street. When Victoria Street was built, between 1835-1840, this ended the old West Bow as a continuous street; A very old house at the top of the West Bow, at the Upper Bow, whose date of construction is not known, was protected by an outer shell of wood, and this was called Mahogany Land. It was demolished in 1878.

The whole of the south side of the Grassmarket had been pulled down and rebuilt several times before 1879, among the oldest buildings being those of the Temple Tenements and the Greyfriars Monastery. The Temple tenements, dating from the 16th century, had formerly been the property of the Knights Templar and subsequently the Knights of St John, following the dissolution of the former order, and were distinguished by having iron crosses on their fronts or gables, one of these crosses still being visible in 1834. The Temple Close was a narrow close that passed beneath the tenements, but all had been entirely swept away by 1870. Uberior House, built as offices for the Bank of Scotland, now the Apex City Hotel, currently occupies this site. The Knights also had premises at the foot of the West Bow.

A tenement was an area of open ground on which a ‘land’ was built, in the 16th and 17th centuries. A land was a building of several stories of separate buildings that were accessed by a communal stair. These could be up to 15 floors high and in the 16th century a lodging (or lugeing) was a single house in a land. A Close was a private passage that was open at only one end and was closed at night. A Wynd differed from a close in that it was open at either end.

One of the most modern houses in this quarter, through which entered Hunter’s Close, had inscribed above the close arch Anno Dom. MDCLXXI (1671) and it was in front of this tenement that the dyer’s pole was set up upon which Captain Porteous was hanged in 1736. In 1847, this line of buildings extending beyond this was extremely varied and antique. Much of this south side has now been completely swept away, and replaced by modern buildings, including hotels, having little architectural merit.

On the south side, near the south-east corner of the Grassmarket, was sited the Grey Friars monastery, opposite the Bow Foot Well, the well having been designed by Robert Milne, established in 1681 and still present on the same site today (although the inscription states 1674, which was the date of bringing water from Comiston). It was repaired and altered by Richardson Bros., of the West Bow, in 1861. This was the first of the wellheads built to supply water in the Grassmarket from the reservoir that used to be sited at Castle Hill, the water coming from Comiston.

The Grey Friars were first noted in Edinburgh in 1429, and it is likely that they moved into the monastery in 1447. It seems that the monastery was so sumptuous that the Franciscan Friars, with their spirit of self-denial and humility, could not be prevailed upon to live in it, and it was only after the intercession of the Archbishop of St. Andrews that they agreed to do so, probably some time after the building had been completed. There, they taught divinity and philosophy until the Reformation in 1560. At this time, their spacious gardens extended up the slope towards the City Wall. The monastery was despoiled in 1559 and in 1562 the gardens were given to the Town Council for use as a burial ground by Queen Mary (Mary, Queen of Scots) although it was not until 1566 that the Magistrates appropriated the garden and removed the Friary buildings.

There seems little doubt that there was a Greyfriars Church on the lands occupied by the monastery of the Grey Friars before the present-day building (building starting in 1613, subsequently ordained on Christmas Day 1620) was constructed. Such a church might be considered an essential addition to the monastery and it likely that one was in place long before Queen Mary gifted the monastery gardens to the city. Some evidence for this lies in the fact that, in the Peace Treaty between James II and Edward IV, the latter proposed that his youngest daughter, Princess Cecilia (aged 4!) should be betrothed to the Crown Prince of Scotland (aged 2) and ratification of this peace treaty was ‘in the church of the Grey Friars, at Edinburgh’.

Additionally, it is recorded that on the 7th July, 1571, craftsmen made their musters ‘in the Gray Friere Kirk Yaird’, and Birrel, in his diary, ‘Diurnal of Occurrents,’ dated 26th April 1598 refers to works in progress by the ‘Societie at the Gray Friar Kirk’.

During 1559, when the Reformation occurred, ‘works of purification’ took place. As a consequence, Trinity College Church, St Giles’, St Mary-in-the-Field and the monasteries of the Black and Grey Friars were pillaged. All that remained of the monasteries were the walls, and in 1560 it was ordered that the stones from these be used to build dykes, and for other good works in the town. In 1562, a good crop of corn (wheat) was sown in the Grey Friars Yard, suggesting that, at this time, it was not in use as a burial ground.

Greyfriars was the first church to be built after the Reformation and it was here that the National Covenant was signed. The church was used as a barracks from 1650-1653, during the invasion of Scotland by Oliver Cromwell. Some 1200 covenanters were imprisoned in the churchyard in 1679; over 100 of these were subsequently hanged in the Grassmarket, with many more being transported overseas to be used a slaves.

Continuing with a chequered history, the Town Council elected to store gunpowder in the tower of the kirk, and the western side of the church was blown up by accident. The west side of the church was consequently rebuilt in 1721 with an additional two bays in the original style.

The church was gutted by a fire in 1845, this destroying both the interior furnishings and the roof. It took many years to restore, and a new single span roof was constructed. The addition of new stained glass windows was also a first – the first parish church to have stained glass windows installed since the reformation. Although there is some slight dispute about this, it is also claimed that this was the first Presbyterian church to have an organ installed to accompany singing.

The Greyfriars (or Bristo) Port led out to an unenclosed common, which bounded the north side of the Burgh Muir, and was only included in the precincts of the city when the last wall of 1618 was built, when the city bought ten acres of land from Towers of Inverleith. In 1530 one Katharine Heriot was accused of theft and of bringing in a contagious sickness from Leith into the city and was therefore ordered to be drowned in the Quarry Holes at the Greyfriars Port, while in the same year the unfortunate Jane Gowane was accused of having the pestilence upon her and was branded on both cheeks at the same place and was then expelled from the city. At a later date, this became known as the Society, and then the Bristo Port.

Many buildings in the Grassmarket were hauled down and new buildings put up in their place, for example, immediately to the west of Heriot Bridge stood a house which was a perfect specimen of its type, having a remarkable antique style of window, with folding shutters and a transom of oak, with glass in the upper part, set in lead.

Near to this building was the Corn Exchange, which had been designed by David Cousin and erected in 1849 at a cost of £20,000. It was 160 feet in length (roughly 50 metres) by 120 feet broad (37 metres) and was built in the Italian style, with a three-storey front and having a campanile (belfry) at the north end. It was set up for mercantile transactions and was the site of many public festivals, including the great Crimean banquet, held there on the 31st of October, 1856.

On the north side of the Grassmarket is situated the White Horse Inn, believed to have been extant when the Highland drovers came to market, armed with broadswords, and gentlemen did not venture out without pistols. It was established in 1516 and was the principal place in which the carriers stayed while country traffic was conducted by their carts or wagons. By 1788 forty-six carriers arrived each week at the Grassmarket and by 1810 this had increased to 96. Coaches left from ‘Francis M’Kay’s, vintner, White Hart Inn’, three times a week at 0900h. Robert Burns stayed at the White Hart Inn in 1791.

Most of the closes on the north side led to the rough slopes of Castlehill, but in the time of Gordon of Rothiemay (mid-17th Century) there was a series of gardens from the west side of the city wall to Castle Wynd, where remained a massive portion of the wall of 1450 (until this was removed to allow the building of Johnston Terrace).

The Plainstanes Close, together with Jamieson’s, Beattie’s, Currie’s and Dewar’s Closes, were all lost as a consequence of the City Improvement Act of 1867. All of these had been located on the north side of the Grassmarket.

Plainstanes Close had at one time been respectable as a paved close, as its name implied and close to it was a tenement, dated 1634. On the west side of Castle Wynd and adjacent to Plainstanes Close was an old house, still present in the late 19th century, which had a door only a metre wide, inscribed ‘Blissit Be God For All His Giftis’ which is double dated – 1610 and 1637, probably suggesting a renewal of the building. This had a fine antique window of oak and ornamental leaded tracery, and there was an adjacent turnpike stair of the same date, having the same inscription, together with the initials L.B.G.K. Castle Wynd led from what is now Johnstone Terrace down to the Grassmarket, and part of the first wall known to be built to protect the city – the King’s Wall of around 1450, began around half-way down the castle bank, which at the time dropped steeply and without interruption to the valley which was to become the Grassmarket. Some remains of this wall can be seen beside the middle portion of Castle Wynd, and also in the region of Tweeddale Court at 14 High Street. Johnstone Terrace itself was built in 1828 and had living quarters for the Castle garrison built in 1873 on the South side.

In Currie’s Close was an ancient door, only 0.85 metres wide, on which was the half-defaced legend ‘God Gives The Res’ and the initials GB and BF, together with a shield and chevron, with what is believed to have been a boars’ head at the base.

In 1763, cockfighting in Edinburgh was completely unknown and yet 20 years later regular matches (known as mains) were held regularly with a cockpit built in the Grassmarket.

The situation in the Grassmarket now is clearly very different from that described above. When the Grassmarket Mission was established, the Grassmarket area was a slum, with chronic overcrowding, sub-standard housing, poverty, unemployment, disease and crime. Today, in the 21st Century, it is a vibrant mix of commercial and residential premises – a far cry from the situation in Victorian times. Despite these changes however, there still remain the underlying problems in Edinburgh of social exclusion as a consequence of poverty, loneliness, hunger and homelessness as well as from substance abuse and ill-health. The ongoing aim of the Grassmarket Mission is to reintegrate people in these groups back into society, restoring their worth and self-esteem and helping them realise their potential.